Elephant

Surreal thoughts from a distant shore

An awe-inspiring evocation of the strong bonds with nature which societies other than ours have retained, Scarlett Hooft Graafland’s photographic oeuvre—like René Magritte’s painterly world—is a place of visionary intensity, startling humour and improbable contrasts, where anything can happen.

The Dutch artist and explorer talks to Muriel Zagha.

Flying bowler hats in the desert, rows of children painted blue, reindeer antlers floating in ice, the artist herself draped over the roof of a church: with projects ranging from rural China to Madagascar, from the Canadian Arctic to the salt deserts of Bolivia, Scarlett Hooft Graafland melds performance, sculpture and photography to create limpid, otherworldly images of carefully staged creative interventions in the midst of harsh, open landscapes.

What started your interest in travel and exploration?

When I was just out of high school I really wanted to become an artist, but my parents thought I should travel first and then make up my mind. So I went to Kathmandu, where my uncle and some other Dutch mountain climbers had set up a small hotel. I stayed there for a bit and then I started travelling in India in pretty rough circumstances. That was the beginning. Through that travelling I became a lot more convinced I wanted to go to art school, and I also met a lot of artists. I was eighteen at the time so it had an enormous influence on me.

You trained originally as a sculptor (in Holland, Israel and America). How did photography become your medium?

I always took photographs to document my installations, my sculptures. Then when I was a student in New York, working on a project about memorials, I became interested in the history of Dutch settlers who had almost eradicated the beaver population through trading. I joined the Beaver Society and managed to get into this community of beaver lovers in upstate New York. It was really crazy. I did all this stuff with beavers—trying to get them to gnaw certain types of special wood, like clogs made out of poplar, which they love, so that they would incorporate it in their dams. Then I’d come back weeks later and all I could do was make photographs—I couldn’t take anything with me. That’s how it started.

Have you retained what you have called “a sculptor’s mindset”?

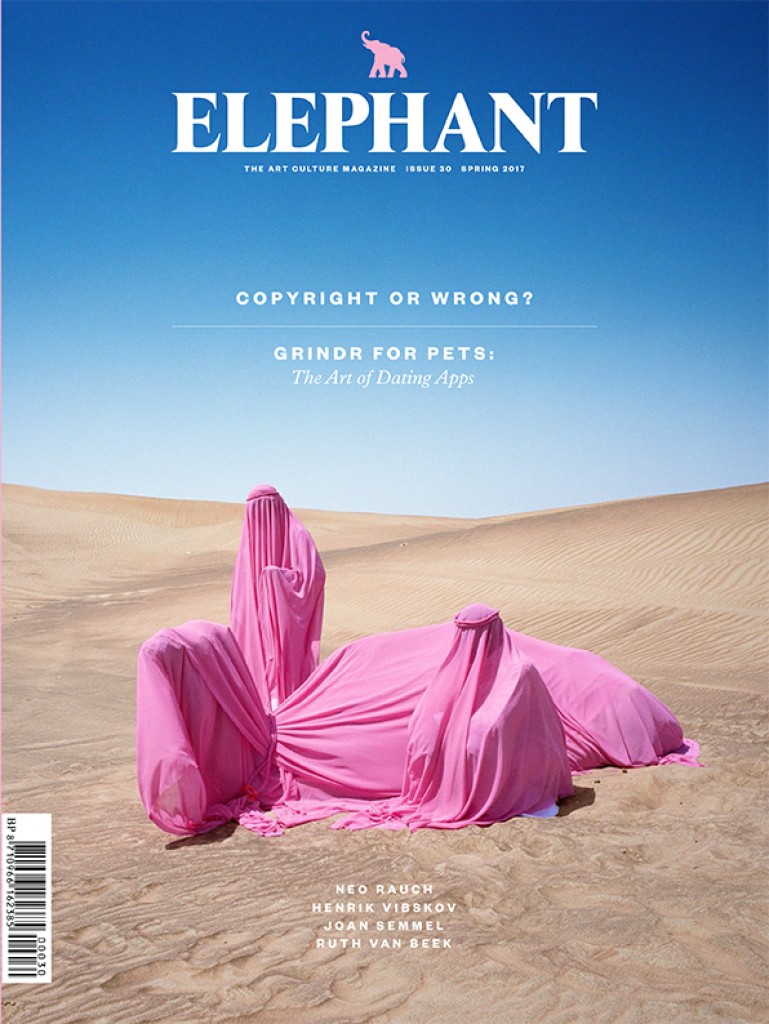

Yes: really I think in volumes. But I’ve also always liked site-specific sculptures: for example, my favourite artwork, Rachel Whiteread’s Holocaust Memorial in Vienna. With the Yemen work—the women in burkas on the beach— I was thinking about volumes, because to me these women in black were almost like sculptures, and then I decided to add the balloons, similar shapes in white, something that by contrast had to do with joy and freedom and parties [Burka Balloons, 2016]. The image of the camel and men wrapped in pink cloth is also about volumes [Still Life with Camel, 2016]. I’d taken part in a show in Dubai, and I wanted to stay on, find local people to work with and do something sculptural. This is a culture that is about what is hidden and what is open, and this type of fabric is so much part of the Arab world for me. The work almost becomes a still life, a still life of people and a camel. It’s like a biblical scene, but also very much about the now, with the tracks of the truck.

So this sculptural work, these installations, often require the participation of local people in cultures where there are many social restrictions. How do you overcome this?

In theYemen picture, the woman in the middle is a photographer herself. She was friends with a friend of mine from New York, so she was my contact person, and it happened through her, because normally women in burkas don’t like to be photographed. In Dubai I was only able to do this work because I’d taken part in a show organized by the sheik: it gave me a way in. On the other hand, when I was making the work with Chinese fishermen, there were people standing around looking on, and later I heard that they were secret police [Nets, 2005]. I felt terrible, and in those kinds of situations it is diffcult to do anything spontaneous. In the Bolivia salt flats at first it was diffcult to convince the women’s husbands to let them participate, but when we left the husbands behind and went away with the women the atmosphere was much better. As you can see, one of the women is laughing [Sweating Sweethearts 2, 2004]: I was really pleased. I like the contrast between a landscape that is so open and so wide, and cultures that have so many restrictions. I always try to find places where it’s not easy, and then see what is still possible.

Do you do a lot of preliminary research before travelling in an anthropological spirit?

I do some. For example, I’d heard about a tribe who live in China high in the mountains near Vietnam. It’s a matriarchy, and I was really inter- ested in seeing that, especially in China. The women there only cut their hair twice in their lives, when they turn eighteen and when they get married, and they carry the cut hair in a roll on their heads—a lifetime of hair. I had the sur- real thought of making a boat out of that hair [Hair Boat, 2006]. It’s like dreaming of going to another place, making the dream out of the hair. Then you have to get people to agree and to like the idea. I was there by myself. These people have their own language, so we couldn’t really communicate. But I think they liked the fact that I was also a woman. I made some small drawings of the idea, very simple things, and it broke the ice.

There is a strong streak of Surrealism running through your work. Is Magritte an influence?

Yes, I’m a big fan. But the pizza picture, for example, was also very personal [My Bonnie, 2005]. I was in China at the time when my father passed away, very unexpectedly, so I immediately went home, but later I came back and I thought I wanted to make an offering to him. You see how the Chinese do that with flowers on a river, so I thought that since pizza had been his last meal I would set one a oat, and it looks absurd in this landscape, where these mountains seem to me like characters by themselves.

Putting yourself in your pictures—lying dangerously on top of a high roof or wrapped in a polar bear skin in the freezing cold—takes some courage.

I do it when I think it works. The polar bear photo is a kind of self-portrait, and it was minus 25, so it was better that I did it myself [Polar Bear, 2007]. I had a very nice Inuit woman as my assistant, I put the camera on a tripod and asked her to take the photo and then she came running to me and put some boots on my feet because it was actually freezing!

With the picture of the red house in Madagascar the reason I wanted to make this photo is because the house is so absurd [Red House, 2013]: how could anyone build such a thing?

I really wanted to do something extreme with it, dangle my legs from the window, you know... But the house is almost ten metres high, and I couldn’t climb out of the window because the tiles were only held in place by sunlight, so they broke immediately when you touched them.The owner of the house helped by cutting a little hole in the roof. Sometimes there is some real physical danger, but if you want something good then you have to do it. I also think that once I’m in those di - cult situations my brain is more focused. I might even need a little bit of danger.

None of this is Photoshopped.You don’t use tricks.

It’s all real. I still use the old analogue way. When the pictures are full scale, you can see the grain of the lm; you know it’s not digital. Nor are any of the photos manipulated. I want to be honest to my audience. Sometimes I have to wait for a long time, just be really focused and, when something happens, immediately respond, using intuition. That’s the only thing you can do. You’re also often limited as to the materials available, so you have to think about what you can use so that it becomes a really strong work. It’s so much more fun this way.

Do you have a favourite place that you’ve been to?

They’re all so different. The most amazing experience was perhaps with the Inuit, when I spent a lot of time travelling with a family on a sled. It was really tough because it never got dark. We spent several weeks on a sea of ice and they didn’t bring any food; we lived on what they hunted and sometimes had nothing to eat. I had my camera, but there wasn’t much time for me to do stuff because they were busy surviving. But I did make a photograph of a seal’s intestine [Palm Tree, 2008].When I saw it I thought it was beautiful and I could make a drawing or a neon sign type of thing out of it. It’s the only thing they throw away, and I liked the idea of using their garbage.

Your interventions are ephemeral: you don’t aspire to leaving your mark on the landscape.

I think it’s beautiful not to do permanent things. You always have to hurry; you never know how much time you have. With the reindeer herd in Norway, when we’d finally got them gathered around the blue plastic reindeer, I took the photo with just a tiny click, a really small noise [Amongst Others, 2010].They heard it and began to run away. I’d been there for weeks! My work is really about a very light gesture, like putting down colourful spices on the salt at to make a pat- tern [Carpet, 2010]. In the end, the wind made the design of this carpet, these beautiful shapes. That is what I love about photography: it’s just one moment, one second, and then it’s gone.

Scarlett Hooft Graafland’s show at Flowers Gallery, London w1,runs from 29 March to 29 April.

An awe-inspiring evocation of the strong bonds with nature which societies other than ours have retained, Scarlett Hooft Graafland’s photographic oeuvre—like René Magritte’s painterly world—is a place of visionary intensity, startling humour and improbable contrasts, where anything can happen.

The Dutch artist and explorer talks to Muriel Zagha.

Flying bowler hats in the desert, rows of children painted blue, reindeer antlers floating in ice, the artist herself draped over the roof of a church: with projects ranging from rural China to Madagascar, from the Canadian Arctic to the salt deserts of Bolivia, Scarlett Hooft Graafland melds performance, sculpture and photography to create limpid, otherworldly images of carefully staged creative interventions in the midst of harsh, open landscapes.

What started your interest in travel and exploration?

When I was just out of high school I really wanted to become an artist, but my parents thought I should travel first and then make up my mind. So I went to Kathmandu, where my uncle and some other Dutch mountain climbers had set up a small hotel. I stayed there for a bit and then I started travelling in India in pretty rough circumstances. That was the beginning. Through that travelling I became a lot more convinced I wanted to go to art school, and I also met a lot of artists. I was eighteen at the time so it had an enormous influence on me.

You trained originally as a sculptor (in Holland, Israel and America). How did photography become your medium?

I always took photographs to document my installations, my sculptures. Then when I was a student in New York, working on a project about memorials, I became interested in the history of Dutch settlers who had almost eradicated the beaver population through trading. I joined the Beaver Society and managed to get into this community of beaver lovers in upstate New York. It was really crazy. I did all this stuff with beavers—trying to get them to gnaw certain types of special wood, like clogs made out of poplar, which they love, so that they would incorporate it in their dams. Then I’d come back weeks later and all I could do was make photographs—I couldn’t take anything with me. That’s how it started.

Have you retained what you have called “a sculptor’s mindset”?

Yes: really I think in volumes. But I’ve also always liked site-specific sculptures: for example, my favourite artwork, Rachel Whiteread’s Holocaust Memorial in Vienna. With the Yemen work—the women in burkas on the beach— I was thinking about volumes, because to me these women in black were almost like sculptures, and then I decided to add the balloons, similar shapes in white, something that by contrast had to do with joy and freedom and parties [Burka Balloons, 2016]. The image of the camel and men wrapped in pink cloth is also about volumes [Still Life with Camel, 2016]. I’d taken part in a show in Dubai, and I wanted to stay on, find local people to work with and do something sculptural. This is a culture that is about what is hidden and what is open, and this type of fabric is so much part of the Arab world for me. The work almost becomes a still life, a still life of people and a camel. It’s like a biblical scene, but also very much about the now, with the tracks of the truck.

So this sculptural work, these installations, often require the participation of local people in cultures where there are many social restrictions. How do you overcome this?

In theYemen picture, the woman in the middle is a photographer herself. She was friends with a friend of mine from New York, so she was my contact person, and it happened through her, because normally women in burkas don’t like to be photographed. In Dubai I was only able to do this work because I’d taken part in a show organized by the sheik: it gave me a way in. On the other hand, when I was making the work with Chinese fishermen, there were people standing around looking on, and later I heard that they were secret police [Nets, 2005]. I felt terrible, and in those kinds of situations it is diffcult to do anything spontaneous. In the Bolivia salt flats at first it was diffcult to convince the women’s husbands to let them participate, but when we left the husbands behind and went away with the women the atmosphere was much better. As you can see, one of the women is laughing [Sweating Sweethearts 2, 2004]: I was really pleased. I like the contrast between a landscape that is so open and so wide, and cultures that have so many restrictions. I always try to find places where it’s not easy, and then see what is still possible.

Do you do a lot of preliminary research before travelling in an anthropological spirit?

I do some. For example, I’d heard about a tribe who live in China high in the mountains near Vietnam. It’s a matriarchy, and I was really inter- ested in seeing that, especially in China. The women there only cut their hair twice in their lives, when they turn eighteen and when they get married, and they carry the cut hair in a roll on their heads—a lifetime of hair. I had the sur- real thought of making a boat out of that hair [Hair Boat, 2006]. It’s like dreaming of going to another place, making the dream out of the hair. Then you have to get people to agree and to like the idea. I was there by myself. These people have their own language, so we couldn’t really communicate. But I think they liked the fact that I was also a woman. I made some small drawings of the idea, very simple things, and it broke the ice.

There is a strong streak of Surrealism running through your work. Is Magritte an influence?

Yes, I’m a big fan. But the pizza picture, for example, was also very personal [My Bonnie, 2005]. I was in China at the time when my father passed away, very unexpectedly, so I immediately went home, but later I came back and I thought I wanted to make an offering to him. You see how the Chinese do that with flowers on a river, so I thought that since pizza had been his last meal I would set one a oat, and it looks absurd in this landscape, where these mountains seem to me like characters by themselves.

Putting yourself in your pictures—lying dangerously on top of a high roof or wrapped in a polar bear skin in the freezing cold—takes some courage.

I do it when I think it works. The polar bear photo is a kind of self-portrait, and it was minus 25, so it was better that I did it myself [Polar Bear, 2007]. I had a very nice Inuit woman as my assistant, I put the camera on a tripod and asked her to take the photo and then she came running to me and put some boots on my feet because it was actually freezing!

With the picture of the red house in Madagascar the reason I wanted to make this photo is because the house is so absurd [Red House, 2013]: how could anyone build such a thing?

I really wanted to do something extreme with it, dangle my legs from the window, you know... But the house is almost ten metres high, and I couldn’t climb out of the window because the tiles were only held in place by sunlight, so they broke immediately when you touched them.The owner of the house helped by cutting a little hole in the roof. Sometimes there is some real physical danger, but if you want something good then you have to do it. I also think that once I’m in those di - cult situations my brain is more focused. I might even need a little bit of danger.

None of this is Photoshopped.You don’t use tricks.

It’s all real. I still use the old analogue way. When the pictures are full scale, you can see the grain of the lm; you know it’s not digital. Nor are any of the photos manipulated. I want to be honest to my audience. Sometimes I have to wait for a long time, just be really focused and, when something happens, immediately respond, using intuition. That’s the only thing you can do. You’re also often limited as to the materials available, so you have to think about what you can use so that it becomes a really strong work. It’s so much more fun this way.

Do you have a favourite place that you’ve been to?

They’re all so different. The most amazing experience was perhaps with the Inuit, when I spent a lot of time travelling with a family on a sled. It was really tough because it never got dark. We spent several weeks on a sea of ice and they didn’t bring any food; we lived on what they hunted and sometimes had nothing to eat. I had my camera, but there wasn’t much time for me to do stuff because they were busy surviving. But I did make a photograph of a seal’s intestine [Palm Tree, 2008].When I saw it I thought it was beautiful and I could make a drawing or a neon sign type of thing out of it. It’s the only thing they throw away, and I liked the idea of using their garbage.

Your interventions are ephemeral: you don’t aspire to leaving your mark on the landscape.

I think it’s beautiful not to do permanent things. You always have to hurry; you never know how much time you have. With the reindeer herd in Norway, when we’d finally got them gathered around the blue plastic reindeer, I took the photo with just a tiny click, a really small noise [Amongst Others, 2010].They heard it and began to run away. I’d been there for weeks! My work is really about a very light gesture, like putting down colourful spices on the salt at to make a pat- tern [Carpet, 2010]. In the end, the wind made the design of this carpet, these beautiful shapes. That is what I love about photography: it’s just one moment, one second, and then it’s gone.

Scarlett Hooft Graafland’s show at Flowers Gallery, London w1,runs from 29 March to 29 April.