Bare Magazine Berkley University

http://www.baremagazine.org/art-la-carte-spotlight-scarlett-hooft-graafland

Art a la Carte: Spotlight on Scarlett Hooft Graafland

You feel much more aware of how small we are as humans—how vulnerable we are amidst these enormous, spacious landscapes.

Raw.

Overwhelming.

Delicate.

Empowering.

I stumbled upon Scarlett Hooft Graafland’s work and was instantaneously envious. I felt the discord between the enclosure of the four-walled library I was sitting in and the landscapes that I was looking at through my computer screen. The spaciousness, the enormity of her images simultaneously terrified and inspired me.

Accustomed to the confinement and predictability of the narrow spaces of a city that I experience everyday, the emptiness of these remote locations presented me with a unique conundrum. Unlike cities where every inch of concrete is perfectly mapped out placating any fears of approaching anything unexpected, these landscapes portrayed the vulnerability that comes along with the possibility of being in a space that is untouched and unexplored. I was overpowered by the mere thought of these environments, yet, somehow, looking at Graafland’s images, I found myself yearning to be lost in the Altiplano of Bolivia.

Inhabiting the border between straight photography, performance and sculpture, Scarlett Hooft Graafland’s photographs are records of highly choreographed live performances in the Salt Deserts of Bolivia, the Canadian Arctic, rural China, Madagascar, Iceland and Vanuatu. In these remote and often surreal landscapes she constantly refers to a more profound cultural discourse of her surroundings, which she utilizes as her canvas.

BARE Interview with Graafland:

What was your inspiration for this project?

Most of my inspiration comes from the power of nature and the vastness of the Altiplano landscapes in the highlands of the Andes. You feel much more aware of how small we are as humans—how vulnerable we are amidst these enormous, spacious landscapes. It is almost as if the landscape ‘dictates’ the outcome of the photograph. And I love to be able to play with these surreal atmospheres. The Salar Salt Desert, for example, invited me in like a piece of drawing paper with the endless, almost blinding whiteness of the place.

I visited Bolivia for the first time after I heard a story about a Bolivian artist, Gastón Ugalde, who utilized Laguna Verde, a green lake, as his ‘gallery’. He created projects at this site and invited other artists and musicians to perform there. The New York Times deemed Ugalde the ‘Andy Warol of the Andes’ because of his method of work, where he utilizes big groups of assistants to help him create his extraordinary installations and sculptures.

The thought of utilizing the lake as a starting point for artwork intrigued me and I managed to shadow Ugalde as he worked with the idea for the lake. On our way, we crossed the Salar Salt Desert and the Red Lake and only two years later I decided to come back and work on projects at these amazing sites.

How did you decide upon the specific materials you gathered from the local neighborhoods you were visiting?

I like to work within a framework of the possibilities that are already on the site. This simultaneously defines and limits the work. With these limitations, you have to find solutions and improvise, based on what materials are available. I always visit the local markets to see which products are typically from the region. This way there is a stronger connection with the environment and it is nice to be able to experiment with new and different materials. Furthermore, it is more practical to work with the materials at the site since I already have to bring a backpack with my camera equipment to the on-site locations, leaving little space for other materials.

Sometimes, there are materials that I chance upon, such as dynamite, that are a pleasant surprise to work with. Because of the intensive mining industry in Bolivia and the shocking, old-fashioned way in which the production is performed in these mines, people sell dynamite for low prices just on the streets. I thought it would be an interesting material to use for my piece, My White Knight, in order to blow up a load of salt on top of the truck, to work with the idea of the transition from a heavy load into a lighter one.

Another material I liked to work with in Bolivia was the so-called ‘aji’, colored spice. In my piece, ‘Blue Truck’, there is a pile of yellow ‘aji’ on the truck. These spices are very common in the Altiplano region, easily accessible in the local markets, and I like the way these bright colors work so powerfully in the salty landscape.

For the piece, Carpet, I used several of these spices to fill out the patterns that are shaped by the wind on the salt flats. The natural design that fills in these shapes almost looks like a man-made design. Coloring in these shapes with the spaces required delicacy. We would begin our work very early in the morning when there was almost no wind, and once the wind picked up later in the day, the carpet began to disappear.

Is there an allusion to environmental effects in your images? How did you decide the manner in which you would portray this issue?

Definitely, I am very much aware of the environment. I like to portray the beauty of nature as well as its vulnerability. I believe that we have to be aware of our surroundings and be careful with what we have.

Do you have a preferred medium or technique?

I prefer photography since it is a medium that is associated with the representation of truth, and in my case, I utilize it to represent the fantastic and the irrational.

I shoot my photos with an analogue medium format camera and print directly from the negative. I prefer this old way of producing images since the colors of the C-prints have such an intense quality. In addition, I like the straight forwardness of the medium—essentially, ‘what you see is what you get’. This ensures that the images are not manipulated digitally and retains the purity and delicacy of the natural moment.

Many of your images adhere to a specific color scheme. Was this premeditated or a result of the natural environment?

I am very attracted to intense color schemes. To find these places we would sometimes have to drive through these locations for days. For example to reach the Laguna Colorada, the Red Lake, or the White Salt Plains, we drove for hours over dirt roads, and chanced upon the landscape with the vivid color schemes that we were pursuing.

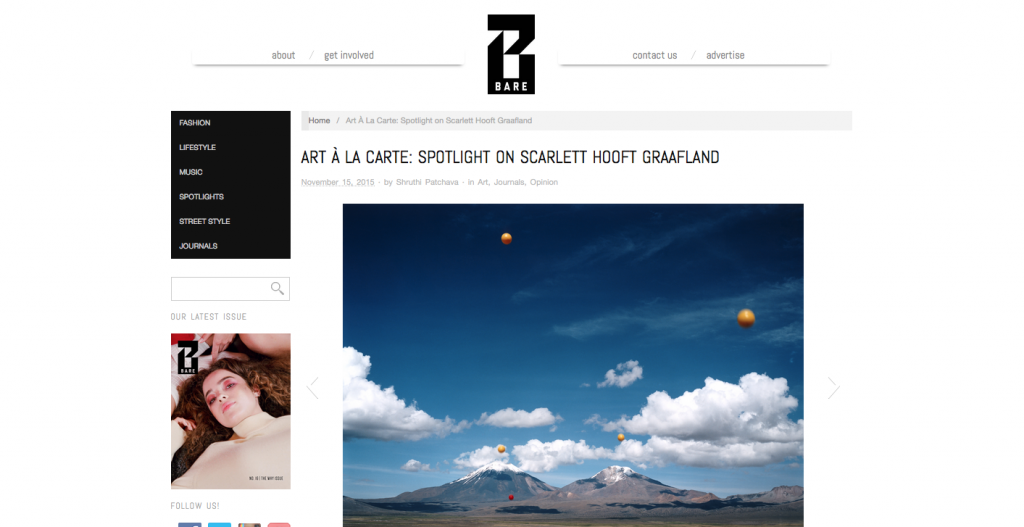

What was the motivating factor that inspired you to pay homage to Robert Smithson for your piece, "Vanishing Traces," and what inclined you towards using floating balloons?

When I was in art school and first saw an image of the, Spiral Jetty, by Robert Smithson, I was amazed by its power. The sculptural gesture that he created in the salt lake and the way in which he embraced the beauty of nature always stayed with me in the back of my mind.

Years later, while visiting the Laguna Colorada, I was reminded of Smithson’s work.

I wanted to pay homage to his work, by placing white balloons in the lake, floating on the red water, as a reference to the Spiral Jetty. However, I wanted my piece, Vanishing Traces, to capture ephemerality. The balloons that we used were intended to be a very light gesture that we would remove after a very short period of time, without leaving any traces. Ironically, once I returned home, I referenced a book about Smithson and his work and learned that he originally intended to create his Spiral Jetty in the same Bolivian lake, but in the early seventies when he was working, the site was too hard to access so he relocated his piece to Utah instead.

Some images that I found to be particularly intriguing were, "Blue Truck," "My White Knight," and "White Pyramid," primarily because of the juxtaposition between the blatant similarities between the materials in the three, yet the subtle, aesthetic distinctions between them. What was your inspiration behind this, and what do you feel each image illustrates uniquely?

It was not my original intention to make so many pieces that utilized the trucks. I started with White Pyramid with the sole idea to use salt as a building material—to utilize it to make shapes with white vastness. By modeling the salt on the top of the truck, it became a sculpture in itself, and took the outlines of a pyramid. The mirroring of the image of the pyramid on the thin layer of water helped to echo the shape.

Working forward from here, I decided to work with some contrasting colors. So, I bought buckets full of yellow spices from the local market in Uyuni. This subtly adds to the surrealism of the image—picture this old, dinky toy truck with the strong yellow pyramid in the back.

After that, I thought that it would be beautiful to search for the opposite—a truck with a very light load, exploding in the air, which comes to life in my piece, My White Knight.

A lot of your works have taken place in Bolivia. What do you feel is the impetus that motivates you to return to these landscapes?

I am attracted to remote places, far away from the Western world, where the local people are not influenced too much by the western civilization. I traveled all over the world and worked on extensive projects in Madagascar, Vanuatu, the Yemenitic Island, Socotra and the Inuit settlement, Igloolik in Northern Canada.

I am attracted to Bolivia in particular because of the incredible landscapes, where the indigenous Aymara people seem to live in balance with nature in these remote locations. Being in these areas, you feel a strong sense of pride for their land, for their culture. Bolivia is the only country on earth where there is a law that defines Mother Earth as "a collective subject of public interest," and declares both Mother Earth and life-systems (which combine human communities and ecosystems) as titleholders of inherent rights specified in the law.

I think it is just a very special spirit to work in!

Experience Graafland's artwork for yourself and check out her site!

Scarlett Hooft Graafland (1973) received a BFA at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, the Netherlands, and a MFA in Sculpture at Parsons School of Design, New York. Her work has been shown at various international exhibitions and photo festivals such as the Hyères festival, the Rencontres d'Arles, the World Expo in Shanghai, the MOCCA Museum in Toronto, the Huis Marseille Museum of Photography in Amsterdam, the MAC museum in Peru, the Museum of Photography in Korea and most recently,was featured at the Landskrona Museum in Sweden.

Art a la Carte: Spotlight on Scarlett Hooft Graafland

You feel much more aware of how small we are as humans—how vulnerable we are amidst these enormous, spacious landscapes.

Raw.

Overwhelming.

Delicate.

Empowering.

I stumbled upon Scarlett Hooft Graafland’s work and was instantaneously envious. I felt the discord between the enclosure of the four-walled library I was sitting in and the landscapes that I was looking at through my computer screen. The spaciousness, the enormity of her images simultaneously terrified and inspired me.

Accustomed to the confinement and predictability of the narrow spaces of a city that I experience everyday, the emptiness of these remote locations presented me with a unique conundrum. Unlike cities where every inch of concrete is perfectly mapped out placating any fears of approaching anything unexpected, these landscapes portrayed the vulnerability that comes along with the possibility of being in a space that is untouched and unexplored. I was overpowered by the mere thought of these environments, yet, somehow, looking at Graafland’s images, I found myself yearning to be lost in the Altiplano of Bolivia.

Inhabiting the border between straight photography, performance and sculpture, Scarlett Hooft Graafland’s photographs are records of highly choreographed live performances in the Salt Deserts of Bolivia, the Canadian Arctic, rural China, Madagascar, Iceland and Vanuatu. In these remote and often surreal landscapes she constantly refers to a more profound cultural discourse of her surroundings, which she utilizes as her canvas.

BARE Interview with Graafland:

What was your inspiration for this project?

Most of my inspiration comes from the power of nature and the vastness of the Altiplano landscapes in the highlands of the Andes. You feel much more aware of how small we are as humans—how vulnerable we are amidst these enormous, spacious landscapes. It is almost as if the landscape ‘dictates’ the outcome of the photograph. And I love to be able to play with these surreal atmospheres. The Salar Salt Desert, for example, invited me in like a piece of drawing paper with the endless, almost blinding whiteness of the place.

I visited Bolivia for the first time after I heard a story about a Bolivian artist, Gastón Ugalde, who utilized Laguna Verde, a green lake, as his ‘gallery’. He created projects at this site and invited other artists and musicians to perform there. The New York Times deemed Ugalde the ‘Andy Warol of the Andes’ because of his method of work, where he utilizes big groups of assistants to help him create his extraordinary installations and sculptures.

The thought of utilizing the lake as a starting point for artwork intrigued me and I managed to shadow Ugalde as he worked with the idea for the lake. On our way, we crossed the Salar Salt Desert and the Red Lake and only two years later I decided to come back and work on projects at these amazing sites.

How did you decide upon the specific materials you gathered from the local neighborhoods you were visiting?

I like to work within a framework of the possibilities that are already on the site. This simultaneously defines and limits the work. With these limitations, you have to find solutions and improvise, based on what materials are available. I always visit the local markets to see which products are typically from the region. This way there is a stronger connection with the environment and it is nice to be able to experiment with new and different materials. Furthermore, it is more practical to work with the materials at the site since I already have to bring a backpack with my camera equipment to the on-site locations, leaving little space for other materials.

Sometimes, there are materials that I chance upon, such as dynamite, that are a pleasant surprise to work with. Because of the intensive mining industry in Bolivia and the shocking, old-fashioned way in which the production is performed in these mines, people sell dynamite for low prices just on the streets. I thought it would be an interesting material to use for my piece, My White Knight, in order to blow up a load of salt on top of the truck, to work with the idea of the transition from a heavy load into a lighter one.

Another material I liked to work with in Bolivia was the so-called ‘aji’, colored spice. In my piece, ‘Blue Truck’, there is a pile of yellow ‘aji’ on the truck. These spices are very common in the Altiplano region, easily accessible in the local markets, and I like the way these bright colors work so powerfully in the salty landscape.

For the piece, Carpet, I used several of these spices to fill out the patterns that are shaped by the wind on the salt flats. The natural design that fills in these shapes almost looks like a man-made design. Coloring in these shapes with the spaces required delicacy. We would begin our work very early in the morning when there was almost no wind, and once the wind picked up later in the day, the carpet began to disappear.

Is there an allusion to environmental effects in your images? How did you decide the manner in which you would portray this issue?

Definitely, I am very much aware of the environment. I like to portray the beauty of nature as well as its vulnerability. I believe that we have to be aware of our surroundings and be careful with what we have.

Do you have a preferred medium or technique?

I prefer photography since it is a medium that is associated with the representation of truth, and in my case, I utilize it to represent the fantastic and the irrational.

I shoot my photos with an analogue medium format camera and print directly from the negative. I prefer this old way of producing images since the colors of the C-prints have such an intense quality. In addition, I like the straight forwardness of the medium—essentially, ‘what you see is what you get’. This ensures that the images are not manipulated digitally and retains the purity and delicacy of the natural moment.

Many of your images adhere to a specific color scheme. Was this premeditated or a result of the natural environment?

I am very attracted to intense color schemes. To find these places we would sometimes have to drive through these locations for days. For example to reach the Laguna Colorada, the Red Lake, or the White Salt Plains, we drove for hours over dirt roads, and chanced upon the landscape with the vivid color schemes that we were pursuing.

What was the motivating factor that inspired you to pay homage to Robert Smithson for your piece, "Vanishing Traces," and what inclined you towards using floating balloons?

When I was in art school and first saw an image of the, Spiral Jetty, by Robert Smithson, I was amazed by its power. The sculptural gesture that he created in the salt lake and the way in which he embraced the beauty of nature always stayed with me in the back of my mind.

Years later, while visiting the Laguna Colorada, I was reminded of Smithson’s work.

I wanted to pay homage to his work, by placing white balloons in the lake, floating on the red water, as a reference to the Spiral Jetty. However, I wanted my piece, Vanishing Traces, to capture ephemerality. The balloons that we used were intended to be a very light gesture that we would remove after a very short period of time, without leaving any traces. Ironically, once I returned home, I referenced a book about Smithson and his work and learned that he originally intended to create his Spiral Jetty in the same Bolivian lake, but in the early seventies when he was working, the site was too hard to access so he relocated his piece to Utah instead.

Some images that I found to be particularly intriguing were, "Blue Truck," "My White Knight," and "White Pyramid," primarily because of the juxtaposition between the blatant similarities between the materials in the three, yet the subtle, aesthetic distinctions between them. What was your inspiration behind this, and what do you feel each image illustrates uniquely?

It was not my original intention to make so many pieces that utilized the trucks. I started with White Pyramid with the sole idea to use salt as a building material—to utilize it to make shapes with white vastness. By modeling the salt on the top of the truck, it became a sculpture in itself, and took the outlines of a pyramid. The mirroring of the image of the pyramid on the thin layer of water helped to echo the shape.

Working forward from here, I decided to work with some contrasting colors. So, I bought buckets full of yellow spices from the local market in Uyuni. This subtly adds to the surrealism of the image—picture this old, dinky toy truck with the strong yellow pyramid in the back.

After that, I thought that it would be beautiful to search for the opposite—a truck with a very light load, exploding in the air, which comes to life in my piece, My White Knight.

A lot of your works have taken place in Bolivia. What do you feel is the impetus that motivates you to return to these landscapes?

I am attracted to remote places, far away from the Western world, where the local people are not influenced too much by the western civilization. I traveled all over the world and worked on extensive projects in Madagascar, Vanuatu, the Yemenitic Island, Socotra and the Inuit settlement, Igloolik in Northern Canada.

I am attracted to Bolivia in particular because of the incredible landscapes, where the indigenous Aymara people seem to live in balance with nature in these remote locations. Being in these areas, you feel a strong sense of pride for their land, for their culture. Bolivia is the only country on earth where there is a law that defines Mother Earth as "a collective subject of public interest," and declares both Mother Earth and life-systems (which combine human communities and ecosystems) as titleholders of inherent rights specified in the law.

I think it is just a very special spirit to work in!

Experience Graafland's artwork for yourself and check out her site!

Scarlett Hooft Graafland (1973) received a BFA at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, the Netherlands, and a MFA in Sculpture at Parsons School of Design, New York. Her work has been shown at various international exhibitions and photo festivals such as the Hyères festival, the Rencontres d'Arles, the World Expo in Shanghai, the MOCCA Museum in Toronto, the Huis Marseille Museum of Photography in Amsterdam, the MAC museum in Peru, the Museum of Photography in Korea and most recently,was featured at the Landskrona Museum in Sweden.